Frank Unwin

(Liverpool, 1920 – Orpington, 2018)

MBE, Liverpool Territorial Army, Royal Artillery

(Liverpool, 1920 – Orpington, 2018)

MBE, Liverpool Territorial Army, Royal Artillery

Frank as an 18-year-old, wearing the uniform of the Territorial Army (May 1939).

Frank enlisted when he was only 18. He fought in Greece (Crete) and Egypt before being captured in Tobruk, Libya, on 21 June 1942. He experienced a profound sense of shame when he was captured and promised himself he would escape.

In August 1942, he was transferred to PG 82 Laterina (Arezzo) after disembarking at Bari. The camp was still being built, and the PoWs were employed in the building site as part of the workforce.

His mother sent him an Italian dictionary, and Frank took up the habit of chatting with the guards, learning the language very quickly. He knew that this was an essential step in his escape plan. In the spring of 1943, he volunteered to work in the detachment of Borgo San Lorenzo (Florence), where surveillance was less strict. Soon, he managed to escape, but a few days later, he was recaptured by some carabinieri on patrol and brought back to PG 82. He was sentenced to 10 days of «rigore»: he was tied to his bed during the night and was forced to answer continuous roll calls.

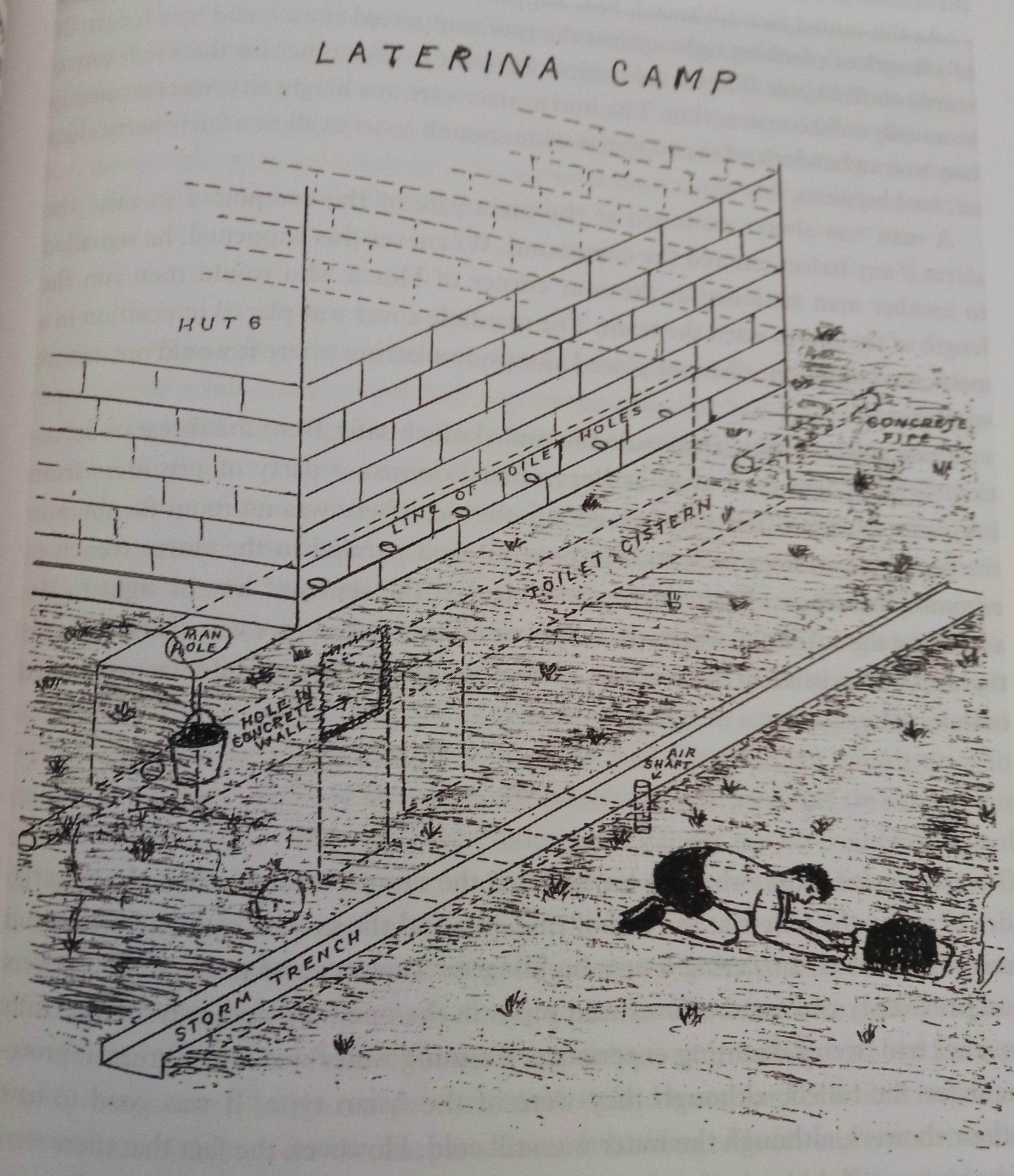

The tunnel dug in Laterina by the PoWs.

However, he was undeterred. He joined a group of 25 PoWs working on a tunnel to escape. Their work was almost done when the PoWs were told about the Armistice. Frank and three other PoWs decided to leave the camp as the Germans were approaching:

[…] Having got the biggest problem [Laterina camp] behind us, our minds were buzzing on what the next steps should be, and we found ourselves in turmoil. The army had always insisted it was a PoW’s duty to attempt to escape, but there had never been a manual of “What to do next”.

The four decided to go south, hoping to meet the Allied troops which had landed in Salerno. They considered they would find better weather this way, rather than trying to cross the Alps to reach Switzerland. They marched through woods and farms, enjoying the mild climate and the help of the local population.

People whom we met immediately recognised us as escaped prisoners, and when we passed a house, we were often greeted with “Come in and take a little glass of wine”. This sort of welcome was an enormous morale-booster and gave rise to the hope that maybe our mission could prove successful.

They marched quickly for some days. However, Frank suffered from nose bleeds which slowed down the group. They decided to stop at a farm owned by Ginestrino Becucci, whom they met in Cennina (Bucine, Arezzo). He insisted that the four should live in his house since, he admitted to their surprise, many in the area had already hid other PoWs, and his family complained he was not doing his part. Ginestrino’s family (his wife and seven children) was poor but welcoming. They also seemed unaware of the risk they were facing.

We had walked into their house and, without any hesitation, been given a room and beds. We never fathomed how much inconvenience was caused to the family or how they rearranged themselves. We had joined the table at mealtimes and shared the family’s already meagre food supplies, and now come to this spontaneous decision to dye our clothing. Their goodwill and concern for our well-being seemed endless.

Ginestrino insisted they had to stay, but Frank, whose condition had improved, declared they wanted to leave. In the end, the four resumed their journey, leaving the farm while the family waved at them.

A few days later, however, they had to stop again, as Frank’s nose bleeds reappeared. He then decided to leave his companions to find a solution.

I was very worried about my health and, with no doctor to advise me, felt I had no choice. A bond had grown between the four of us as we had shared the sweat and toil in the tunnel and then travelled together since leaving Laterina, and I was filled with emotion as I wished them good luck. I watched them go round the bend past the blackberry bushes. I never learned what happened to them.

While retracing his steps to reach Ginestrino’s house, Frank ran into Lello, who immediately recognised him as an English and brought him to his friend, Vittorio, who hid and fed him. Moreover, Vittorio told him that, in that area, another six PoWs were hidden in a hut in the vineyards near Pietraviva. The escapees were fed daily by the population.

It was Sunday. Small groups began appearing, coming from isolated farmhouses and from near villages. The whole afternoon was devoted to receiving visitors and accepting the food they brought. A few families brought billy cans of fresh warm pasta. Besides that, there was bread, pecorino cheese, salami and sausages, as well as grapes, figs and peaches. The wine was plentiful also.

Onelia Pieraccini and Corrada Landi, from Montebenichi, also took part in this procession. Frank met them again a few days later as he brought back some empty wicker wine bottles. The two girls invited him to stay in their village, and the people cared for him as they did with the other PoWs. He was housed in a hut at the village’s entry.

During his stay in Montebenichi, Frank made daily visits to the nearby villages and became an attentive observer of the local customs, taking part in the village’s life and escaping a few encounters with the Germans who searched the area from time to time looking for escaped PoWs.

Montebenichi. On the bottom right, the hut belonging to the Landi family where Frank was housed.

Nor was there any fresh water supply. The water from a very picturesque well in the village square was no longer potable, and all water had to be carried from springs on the wooded slopes outside the village.

Every family kept a few pigs, chickens, rabbits and pigeons, and three or four sheep. The sheep were not raised for food but for the wool that they provided at an annual shearing and which was used for a great part of the family’s clothing.

The only form of transportation in the village was ox-carts.

In spite of the many difficulties that made for a hard life, the villagers seemed to accept their lot with grace and just got on with things.

Frank grew impatient in the spring of 1944: the Allies’ advance, which he had imagined would be quick, had stalled. Moreover, he knew his family was unaware of whether he was alive or dead. Thanks to the help of the population, he was now back in shape, and his health had improved. This convinced him to resume his journey toward the south, which he had interrupted five months before. Two other PoWs, Roy and Don, joined him from the nearby village of Pietraviva.

My announcement was met with disbelief. I found that the villagers of Montebenichi had called a meeting to be held in the Dopolavoro and its purpose was to dissuade us from leaving. One by one, the men spoke, emphasising the distance, the unknown terrain and above all, the difficulty of getting through the German lines. Women pleaded with us to stay and give up this foolhardy idea. Some of them were in tears.

However, we had not come to our decision lightly, and the thought of our families having no news of our fate for so long was not to be put aside. So we told them that we appreciated all they had said, but it had not lessened our resolve to go ahead with our plan. We also offered our heartfelt thanks to them for the care and sustenance they had given all of us, especially myself.

It was dusk on a glorious cool crisp day when we left our shack in the woods for the last time. As we approached the village, we saw there were people waiting to see us off. Onelia e Corrada each, in turn, embraced me very warmly and I realised what wonderfully good friends they had been. We were all in good spirits and feeling ready for whatever lay ahead of us.

Frank and his comrades marched towards the Allies’ lines, but their journey was cut short. They were soon intercepted by some men of the Fascist Guardia Nazionale. Captured, they were transferred to Siena, Florence and Mantova and then to Germany, to Stalag XIA, Altengrabow, near Magdeburg. Soon, Franck was transferred to a work camp, a cement factory in Jesabruch, and then a stone quarry in Anhalt, where living conditions were terrible. However, even there, he continued to plot his escape. In March 1945, as the Allies were approaching, Frank was ordered to abandon the camp and was among those who took part in the “long march”. After a few exhausting weeks, he was finally freed by the American troops on 12 April 1945.

Now that I was safely home, I knew that I owed a great deal of thanks to the people of Montebenichi and the other villages and farmsteads of Valdambra, whose kindness and sacrifice had brought me to the peak of fitness. Without their help, I would surely have found the hardship in Germany an ever greater challenge to my survival.

From 1949 until his death, Frank regularly returned to Valbrembana to visit those who saved his life and their descendants.

Related camps

Places

- Italia: PG.82 Laterina (AR), Borgo San Lorenzo (Fi) work camp, Val d’Ambra (Bucine, Cennina, Pietraviva, Montebenichi),

- Germany: Stalag XI A Al

Sources:

- F. Unwin, Escaping has ceased to be a sport, Pen & Sword, Barnsley, 2018

- F. Unwin, Roll on stalag, memoria privata (2011)

- PG89 Laterina – https://campifascisti.it/scheda_campo.php?id_campo=365