Arthur Wallace Scott

Lance Corporal, 24 New Zealand Infantry Battalion

Arthur «Arch» Scott, a young New Zealander corporal, enlisted as a soldier. However, he was captured in December 1941, during his first battle in Egypt near El Alamein.

After spending some time in the Libyan camps and three weeks in the Benghazi PoW camp, on 16 August 1942, he was embarked on the «Nino Bixio», a cargo ship bound to Italy. Their journey was cut short by a torpedo during the second day at sea. Almost all the men on board died, and Arch was among the few who survived.

Arthur Scott in 1941, before his departure to the front (Source: L. Antonel, I silenzi della guerra)

At the end of August, he reached PG 75 Bari, and, a few weeks later, he was transferred to PG 107 Torviscosa (Udine), where many New Zealander PoWs were held. To fight against the monotony, he started plotting his escape and learning Italian. At the end of June 1943, he was part of a group of 50 PoWs who were transferred to the work detachment 107/7 in La Salute di Livenza. Here, thanks to his knowledge of Italian, he became the group’s interpreter and was relieved from working in the fields.

When the Armistice was announced on 8 September, the gates of the detachment were opened, the barbed wire cut and the PoWs freed.

We were “free” but among enemies. We were free but were like helpless animals that had been freed in a vast area full of predators […]. Having a bounty on our heads taught us quickly what it meant to be “hunted”.

During the following days, the group decided not to split and to remain in the area because of the help that the local farmers provided them. Arch, nicknamed «the English Captain», became the interpreter between the PoWs and the locals, as the only one who knew both languages. He soon became friends with Don Antonio Andreazza, the priest of Sant’Anastasio di Cessalto «who was neck-deep in the liberation committees». Antonio helped Arch to improve his Italian and provided him with two fake ID cards: Arch became «Arturo Scotti».

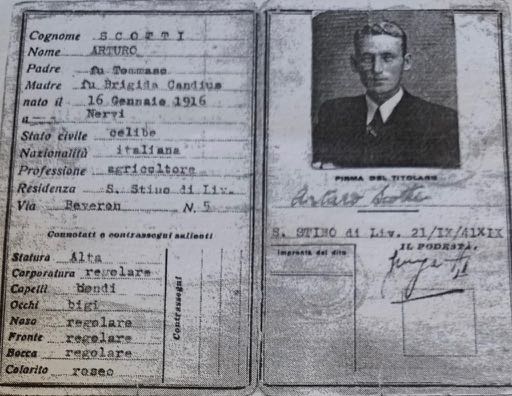

One of the fake ID cards provided to Arch by Don Antonio.

During their first meeting, Arch and Antonio started organising plans to evacuate the other escapees from the area. In October 1943, Arch made five trips to escort about 50 men in the hills around Monfalcone, where, allegedly, some partisans were evacuating escaped Allied PoWs, sending them to Croatia via sea. However, he discovered that the former PoWs were forced to join the partisan bands and were not evacuated. In addition, Arch was busy trying to contact England via radio and, thanks to the help of the Martini sisters from Padua, he also managed to organise a mass evacuation which, unfortunately, ended with the capture of all the escapees.

Arch was fully integrated into the local community. His dialect was impeccable; many times, despite being side by side with the Germans, he was mistaken for an Italian. After a few months with Antonio, a tip-off led to the arrest of many former PoWs and their helpers in the village. Thus, Arch moved to the attic of the Visintin family, where he lived for about three weeks.

The Visintin family treated me very well. I spent most of the time studying the language, reading, and admiring the beautiful, farmed fields from the attic’s window.

However, the area was not safe any more, and Arch, together with another New Zealander, Noel Sims, had to move. They hid in the San Anastasio school for about 10 days, where Antonio’s sexton brought them food regularly. During the following days, the priest contacted a family of sharecroppers who lived on the opposite bank of the Livenza river. In April 1944, and for the next year, the Antonel – three brothers with their respective wives and 10 children – took care of Arch and Noel, welcoming them into the family.

I thought we would stay only for a short period, but things dragged on, and we were forced to stay there or nearby for about a year. […] The Antonel family lived in a big, two storeys brick house. […] Around the table, there was room for almost everyone to sit at dinner. The wives, in fact, rarely sat down to eat, as they had to care for the family’s needs.

Near the house, there was the stable, which during winter evening became the “living room” where the whole family gathered: women and girls knitted, spun, and sewed; men and boys chatted or recalled the events of the day.

[…] It was the first time we lived close to children, and we soon learned to love them. They were very helpful in improving our knowledge of Italian and even better of the Venetian dialect. The older ones attended the village’s school, and one day when I asked Angin if he had been promoted, he told me, no, giving then the most natural and logical explanation for his failing: “I did not bring a chicken to the teacher!”

Arch was among the most wanted escapees of the area; the bounty on his head reached one million lire. Between October and November 1944, he often travelled to Friuli and near Belluno, trying to organise the evacuation of the former PoWs hiding in the area.

In February 1945, he contacted the Albatross mission, sponsored by the American secret services (OSS), led by Captain Chappell, who managed to prepare an effective evacuation plan. Arch’s task was to group the PoWs into teams of 12 or 15 men and then lead them to a beach, at a rendezvous point, and then wait for a boat to pick them up. It was a complex plan, complicated by the fact that often the boat could not reach the coast, and the men were forced to run back to their hideouts quickly. However, with this method, during moonless nights, Arch managed to evacuate 47 former PoWs. He refused many times to take the boat and leave, as he considered his duty to stay until he had evacuated all of his comrades.

During his stay in San Stino, Arch contacted the local partisans and established a relationship with their leader, Gino Panont «Treviso»:

Gino was the one I knew best. […] Although he was very busy and was not directly involved in our evacuation plan, we could count on him providing men to escort us or using his experience to solve seemingly unsolvable problems.

On 13 April 1945, Arch joined one of the last evacuations and reached Ancona via sea, where he was assigned to the American Office of Strategic Services. Later, he was allowed to go back and fight with the partisans. However, the plan to airdrop him failed. Nonetheless, Arch decided to reach the north of Italy following the Allied advance. During this period, he visited San Stino di Livenza to meet the families who had welcomed him before.

After the Liberation, in April 1945, he moved to Portogruaro, where the Allied Military Government appointed him vice-governor of the areas of Portogruaro, San Donà di Piave and San Stino di Livenza. When the actual governor, Lt. Harold Lavander arrived, Arch remained by his side for a while as an interpreter and assistant.

Soon, the order that all former PoWs from New Zealand had to be repatriated via England arrived. On 27 June, I was ordered to go to the headquarters before the end of the month.

Arch did not want to leave Italy and tried to get a permit to stay from the Allied authorities but to no avail. At the end of June 1945, he was transferred to Rome and then to England, where he remained for about three months. He boarded a ship to New Zealand in November 1945 and arrived home before Christmas.

After the war, Arch returned to Italy three times, in 1966, 1981, and 1983 with his wife and children:.

My family was moved many times, essentially every time I encountered some old Italian friend who, with tears running down their cheeks, hugged me and cried openly, without being ashamed, saying only: “Arturo! Arturo! Arturo!”

Related camps

Sources

- Roger Absalom, A Strange Alliance. Aspects of escape and survival in Italy 1943-45, Firenze, Olschki, 1991 (trad. it., L’alleanza inattesa. Mondo contadino e prigionieri alleati in fuga in Italia 1943-1945, Bologna, Pendagron, 2011).

- Lucia Antonel, I silenzi della guerra: prigionieri di guerra alleati e contadini nel Veneto orientale, 1943-1945, Portogruaro, Nuova Dimensione – Ediciclo, 1995.

- Arch Scott, Dark of the moon, [s.l.], Cresset, 2000.