Sheet by: Costantino Di Sante

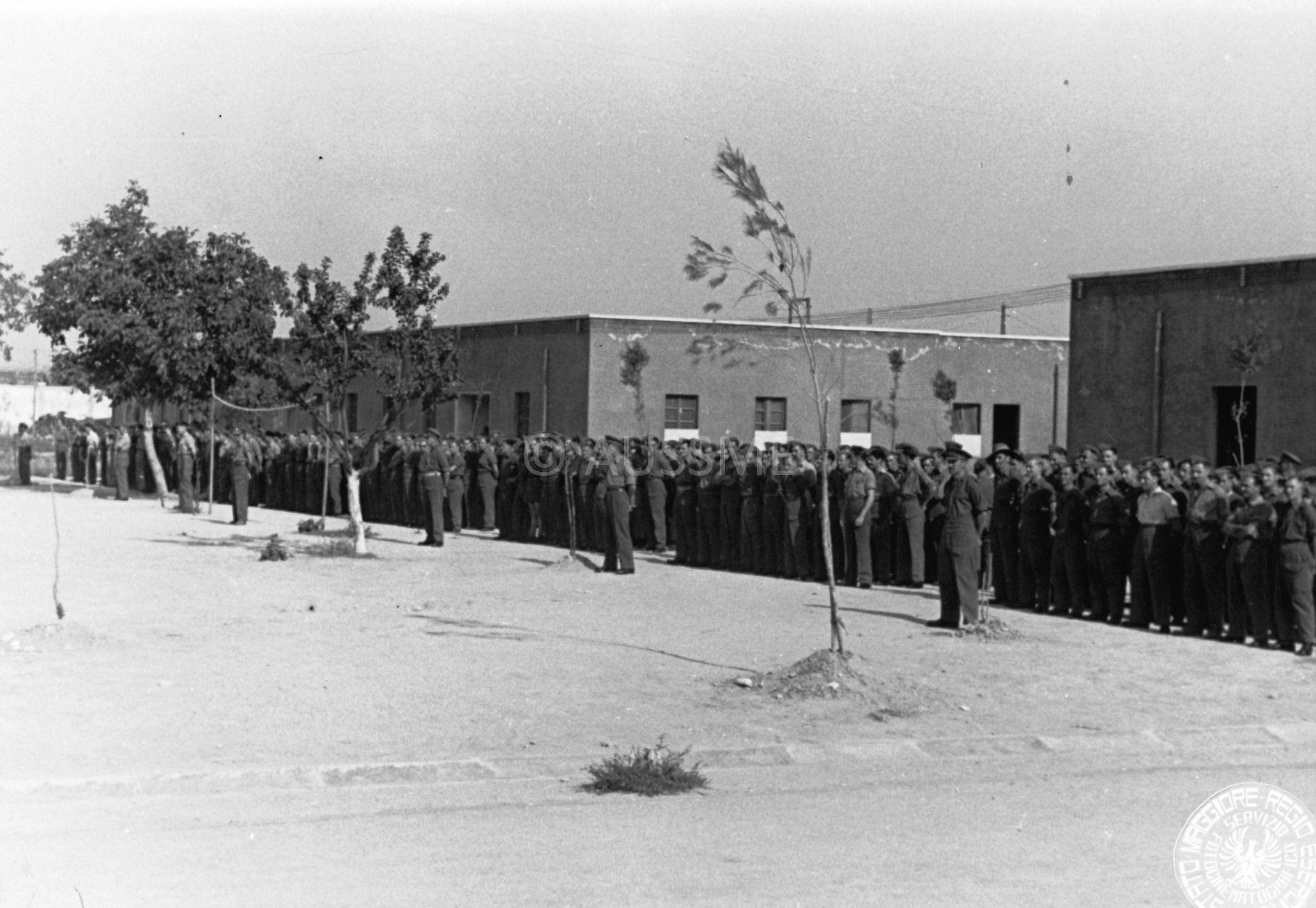

Assembly of prisoners of war at concentration camp No. 21 in Chieti - AUSSME Archive, Fototeca 2 Guerra Mondiale Italia 507/649

General data

Town: Chieti

Province: Chieti

Region: Abruzzo

Location/Address: Chieti Scalo - Chieti

Type of camp: Prisoner of War camp

Number: 21

Italian military mail service number: 3300

Intended to: officers

Local jurisdiction: IX Army Corps

Railroad station: Chieti

Accommodation: military quarters

Capacity: 1000

Operating: from 07/1942 to 09/1943

Commanding Officer: Mario Barela (July – September 1942); Lt. Col. Giuseppe Poli (October – December 1942); Col. Giuseppe Massi (January – September 1943)

Brief chronology:

August 1942: the first Allied PoWs arrived.

September 1942: the camp was overcrowded; it held more than 1,600 PoWs.

14 September 1942: the PoWs staged a mass protest.

20 February 1943: a group of PoWs was sent to work in the mines of Acquafredda di Roccamorice (Pescara).

21 September 1943: the Germans occupied the camp.

23 September 1943: the Germans began deporting the PoWs to Germany.

Allied prisoners in the Chieti camp

| Date | Generals | Officers | NCOs | Troops | TOT |

| 1.9.1942 | 1233[1] | 8 | 248 | 1489 | |

| 30.9.1942 | 1343[2] | 8 | 249 | 1600 | |

| 31.10.1942 | 992[3] | 8 | 240 | 1241 | |

| 30.11.1942 | 984[4] | 8 | 248 | 1240 | |

| 31.12.1942 | 966[5] | 8 | 249[6] | 1223 | |

| 31.1.1943 | 985[7] | 11[8] | 261[9] | 1257 | |

| 28.2.1943 | 1002[10] | 11[11] | 261[12] | 1274 | |

| 31.3.1943 | 964[13] | 11[14] | 321[15] | 1296 | |

| 30.4.1943 | 1063[16] | 14[17] | 257[18] | 1344 | |

| 31.5.1943 | 1041[19] | 14[20] | 2687[21] | 1342 | |

| 30.6.1943 | 1074[22] | 20[23] | 288[24] | 1382 | |

| 31.7.1943 | 1117 | 1117 | |||

| 31.8.1943 | 961[25] | 42[26] | 319[27] | 1422 |

Camp’s overview

During the spring of 1942, due to the lack of materials and suitable areas to build PoW camps, the PoW Office of the Italian Chief of Staff was forced to use existing buildings. Some suitable structures to house a PoW camp were identified in Chieti Scalo, despite some doubts caused by the presence of a nearby train station.

The buildings, labelled «casermette funzionali» (small functional barracks), had been built between 1937 and 1938 by the Odorisio firm for the Ministry of War. They were initially intended to house the 14th Infantry Regiment but had not been used since the beginning of the war. During the spring of 1942, the site, which extended for 17 thousand square metres and had 120 rooms (spread across the «casermette»), was refurbished to hold the PoWs.

Its capacity was stated at 1,000 and the camp officially opened in July 1942. After two months, it already held 1,600 British PoWs, 1,200 British and 386 South Africans.

Despite the transfer of some PoWs, the camp remained overcrowded, and, according to a Red Cross inspector, it could not hold officers because it lacked proper furnishings and was short on water. Although the Protecting Power delegate protested at this, some issues remained unresolved for months after the camp’s opening.

This was made evident byCaptain C. Napier Cross, in a report he wrote after the war:

During the spring of 1943, the Italians did little to improve the situation, except for placing a few stoves in the dormitories. So much so that the Protecting Power delegates were ready to demand the camp’s closure.

However, PG 21 remained open, and the PoWs could find solace only in a few recreational activities. Among these was was the newspaper «Chieti News Agency», shortened as «CNA», established by Major Gordon Lett. Moreover, the PoWs tried to raise their morale with theatrical and musical shows organised by some artists held in the camp.

The guards’ behaviour as well was questionable at best. After the umpteenth vexation by the guards, who continued to pilfer the Red Cross parcels, on 14 September 1942, the PoWs staged a mass protest. They refused to work and staged a sit-in in the roll call square. The camp’s command ordered the guards to fix their bayonets and surround them. As the PoWs did not flinch, Commandant Barela decided to come to an agreement with the PoWs’ representative and conceded that, from then on, the PoWs would obey only their direct superior’s orders. Barela was replaced with Lt. Col. Giuseppe Poli, but it is unclear whether this happened because of the PoWs’ protest.

However, the new commandant did nothing to stop the vexation. For example, the PoWs were forced to answer roll calls at night, even during the winter, standing in the snow for hours.

At the end of the war, the camp’s commandants and their collaborators, in particular Captain Mario Croce, were all investigated for brutality. As the investigation could not find proof or witnesses (many were dead or missing), in May 1946 they were all acquitted.

Although surveillance was rigorous, in September 1942, there were two escape attempts. One officer hid in a fruit lorry but was spotted and seized. On 14 September, Lt. Joseph Farrell escaped wearing an Italian uniform. He stole a bike and reached Pescara train station, where he got on a train. He managed to reach Parma, where he was captured and brought back to Chieti. In the spring-summer, the PoWs dug four tunnels. However, despite the presence of many “professional” escapers, it seems that no one managed to escape before 8 September 1943.

In February 1943, a group of PoWs was sent to the work detachment of Acquafredda di Roccamorice (Pescara), subordinate to PG 78 Sulmona, to work in the nearby mines managed by the firm Alba.

After the Armistice, most of the Italian guards deserted. Only the camp’s commandant, some 20 officers and 30 soldiers remained. They threatened to open fire if the PoWs attempted to escape. Senior British Officer, L.t Bob Marshall ordered the PoWs to stay put. He believed the Allies would reach the camp in a few days and feared that a mass escape could cause a violent German reaction. It was only on 18 September that some PoWs escaped using the tunnels they had dug before. Three days later, the Germans occupied PG 21. On 23 September, they began deporting the PoWs to PG 78 Sulmona (L’Aquila) and then to Germany. Even though some managed to escape during the transfer, most of PG 21’s PoWs ended up in German PoW camps.n .

In the following months, the Germans used the site as a transit camp for Jews, draft dodgers, and partisans captured in Chieti province and near the Gustav line.

After the Liberation, the «casermette funzionali» became the homes of refugees who had fled to Chieti during the Nazi-Fascist occupation. After the war, the barracks were renovatede and given to the Centro Addestramento Reclute (CAR – Recruit Training Centre). They were later dedicated to Enrico Rebeggiani, an officer of the Alpini, who had been awarded a gold medal for military valour. The barracks became the seat of the II Battalion of the carabinieri junior officers and, today, it is the National Administrative Centre of the carabinieri.

Archival sources

- Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Ministero dell’Interno, Direzione Generale Pubblica Sicurezza, A5G, II GM, bb. 116, 117, Verbali e Notiziari della Commissione Interministeriale per i Prigionieri di Guerra

- Archivio Centrale dello Stato, MG, CGCC, Miscellanea, scatola 1

- Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Ministero dell’Aeronautica, Gabinetto, b. 70, Verbali e Notiziari della Commissione Interministeriale per i Prigionieri di Guerra

- Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Onorcaduti, b. 1

- Archivio Storico Ministero Affari Esteri, (1931-1945), Prigionieri e internati (1940-1943), b. 21

- Archivio Ufficio Storico Stato Maggiore dell’Esercito, H8, b. 79

- Archivio Ufficio Storico Stato Maggiore dell’Esercito, L10, b. 32

- Archivio Ufficio Storico Stato Maggiore dell’Esercito, N1-11, bb. b. 740, 843, b. 1130

- The National Archives, WO 311/316

- The National Archives, WO 224/108

- The National Archives, TS 26/755

- The National Archives, WO 224/111

- The National Archives, WO 208/5585

Bibliography

- Absalom R., A Strange Alliance. Aspects of escape and survival in Italy 1943-45, Firenze, Olschki, 1991 trad. it. L’alleanza inattesa. Mondo contadino e prigionieri alleati in fuga in Italia (1943-1945), Bologna, Pendagron, 2011

- Insolvibile I., I prigionieri alleati in Italia 1940-1943, tesi di dottorato, Dottorato in "Innovazione e Gestione delle Risorse Pubbliche", curriculum “Scienze Umane, Storiche e della Formazione”, Storia Contemporanea, Università degli Studi del Molise, anno accademico 2019-2020,

- Lett B., An extraordinary Italian imprisonment: the brutal truth of Camp 21, 1942-3, Barnsley, Pen&Sword, 2014